An Achievement Of Olympic Proportions

The 1972 Olympic buildings, spectacular in their day and embodying the motto of the Munich Olympics – “The Cheerful Games” – are now to be declared a World Heritage Site. That the architects also had WACKER dispersible polymer powders to thank for making their ambitious plans a reality is a little-known facet of the story.

The Olympic Village in northern Munich: the intelligent-design urban complex ranks among the city’s most sought-after residential areas.

A one-room, 33-square-meter apartment on the 10th floor in Munich’s Olympic Village set a buyer back €195,000 at the beginning of 2018. A steep price for an apartment in one of those typical – and generally unpopular – housing developments of the early 1970s that can hardly be called “villages.” At first glance, visitors see a lot of densely packed, prefabricated concrete slabs. A second look, however, reveals sophisticated urban planning: “Living in the Olympic Village has cult status,” asserts a Munich real estate report. Some 6,000 residents have lived here for many decades – roughly 90 percent of all moves are simply relocations within the Village.

Like the Olympic Stadium to the south, with its spectacular tent-like roof, Munich’s Olympic Village became a designated historical site in 1997. But for the Olympic Village residents’ association and the Olympic Park World Heritage Campaign, that doesn’t go far enough: they want the Olympic Park, including the stadium and village – described in Bauwelt architectural magazine as the “most significant architectural ensemble” created by the Federal Republic of Germany – to be added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In late 2017, Munich City Council sought expert advice. Nearly all testimonies recommended applying for the status.

The top-quality cement used for the Olympic buildings – a prestigious project for Germany – still endures after over 40 years.

Munich has been more successful in repurposing its Olympic venues after the games than most former Olympic host cities. A scenario considered highly unlikely 50 years ago, shortly after the Behnisch und Partner architecture firm won the architectural competition for the Olympic complex. Skeptics even doubted whether the spectacular design made of acrylic glass could be built at all. “It wasn’t just the tent roof – there were also issues with the concrete and mortar that no one had ever faced before,” recalls Karl-Heinz Kranz, who is now 77 years old.

1968 marked both the start of excavation on the Olympic Park and an important year for him personally: Ardex, a construction chemicals manufacturer based in Witten, northwestern Germany, hired Kranz, who was a skilled bricklayer, tiler and master screed layer. Ardex, and Kranz, would later make a small but significant contribution to the construction of the Olympic site – one destined to tremendously expand the scope of the dry-mix mortar industry in the years to come.

Light and transparent

The attraction of this residential complex lies in its smaller row houses that serve as student accommodation and its stepped apartment buildings featuring large south-facing balconies.

With their light, airy and, in the case of the Olympic Stadium, sweeping architecture, Munich’s Olympic venues were designed to symbolize “cheerful games,” according to Willi Daume, the then head of the German Olympic Committee. As the only summer games held to date in postwar Germany, the event aimed to show the world a new, friendly, cosmopolitan face. The organization of the games was pursued as a collective national effort and was enthusiastically supported by virtually all Munich’s citizens.

Karl-Heinz Kranz was one of the many thousands of specialists who helped build the completely new Olympic complex in the north of Munich – quite literally from the ground up – in less than five years. His job was to renovate a load-bearing pillar in which holes and cracks had been discovered. Given the Olympic construction site management’s instructions forbidding repair work, the project had to be kept secret. Indeed, management had already issued orders to tear down and rebuild one faulty concrete wall. “A three-month delay and several hundred thousand marks were riding on that pillar,” Kranz recalls.

Smoothing compounds to the rescue

The color scheme for the Olympic buildings was created by the renowned Munich designer Otl Aicher, who was lead designer during the 1972 Olympics.

The Ardex specialist was flown in, and once on site he turned to Arducret B12, a cementbased concrete filler that he himself had helped develop at Ardex and which had been available for only a few months. The product contained a dispersible polymer powder made from vinyl acetate-ethylene (VAE) copolymer, which WACKER had likewise only recently begun producing.

“The VAE copolymer in the mortar acts as a second, flexible binder in addition to the rigid cement,” explains Dr. Peter Fritze, who heads a WACKER applications laboratory for construction polymers. It improves both the cohesion and flexibility of this specialty mortar, he notes, and the polymer modification also reduces the amount of water needed for the filler, which, in turn, reduces shrinkage. “Thanks to these improved properties, the filler is able to repair defects in the concrete permanently,” the WACKER chemist stresses.

In the early 1970s, polymer-modified concrete fillers were still uncharted territory. Nevertheless, Kranz got down to work. “Even though atmospheric conditions and the sun were on my side, it was evening by the time I made it down to the support. I was just making my final pass with the trowel when someone hissed: ‘Get away from the pillar – site management’s coming!’

The light, airy architecture of the Olympic buildings, like the swimming pool, for example, were intended to create a pleasant atmosphere.

A revolution on the construction site

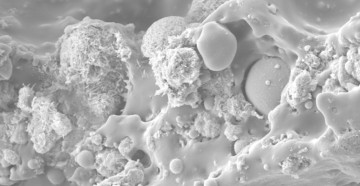

Polymer-modified cement mortar under a scanning electron microscope: The VAE polymers in the image have a smooth surface. They act as binders and increase the flexibility of the set mortar.

But the site management representative was not fooled. The man turned and called out to his colleagues, “They’ve been patching this up. But just take a look at how good it is – it’s almost better than the concrete itself.” Kranz sees the episode as a breakthrough for Ardex concrete filler at the Olympic building site.

Another Ardex product used was Ardurit X7G, a tile adhesive Kranz also had a major role in developing. “The product – today we’d call it a flexible adhesive – had been considerably enriched with VAE copolymer,” says Kranz.

“VAE copolymers in the mortar act as a second flexible binder in addition to the rigid cement.”

Dr. Peter Fritze, Technical Service at Construction Polymers, WACKER POLYMERSLean layers

VAE

VINNAPAS® vinyl acetate-ethylene (VAE) dispersions and dispersible polymer powders are copolymers produced by emulsion polymerization of vinyl acetate (a hard polar monomer) and ethylene (a soft hydrophobic monomer). Vinyl acetate and ethylene are polymerized at high pressure in water using colloidal stabilization. Ethylene is an ideal plasticizer for vinyl acetate, which imparts long-lasting durability to VAE polymers. As a result, vinyl acetate-ethylene doesn’t need an external plasticizer.

VAE polymers have outstanding film-formation properties – no solvents are needed. This means formulators can develop and manufacture water-based products with a very low VOC content that adhere well to non-polar substances. The glass transition temperature varies from +25 to –25 °C as a function of the ethylene content.

Up to that point, the thick-bed technique was used for tiling all over the world: tiles were placed in a layer of mortar at least 1.5 centimeters thick, consisting almost exclusively of cement, sand and water. “That kind of slightly moist material is difficult to process and almost impossible to apply with a spatula,” says Dr. Fritze from WACKER’s Technical Service. Also, he notes, the mortar tends to bleed. In other words, the water content migrates to the surface of the mortar and/or is absorbed by the substrate. “That could prevent the cement from setting sufficiently, especially if the mortar layer is thin,” says Fritze, adding that the adhesive mortar has to be a few centimeters thick in order to have enough water to harden sufficiently.

The thick-bed technique was both prone to error and time-consuming. “It wasn’t until we had VAE polymers that we could process cementitious materials into layers less than a half centimeter thick,” observes Kranz. These polymers improved tile adhesion on the substrate and helped dissipate any stress that might arise. Thin-bed technology – the standard of today – was born. “The technology meant that tilers could cover larger areas in the same amount of time – a huge advantage, given rising labor costs,” Fritze adds.

The opening ceremony of the Munich Olympic Games on August 26, 1972. The Olympic Stadium with its curved polyacrylic glass roof was revolutionary at the time.

The rise of densely sintered porcelain stoneware tiles and their reduced porosity – and hence greater resistance to freezing – made polymer-containing tile adhesives like Ardurit X7G a necessity. Fritz and Kranz are of one opinion: “There’s no way you could lay these tiles with the old thick-bed technology.” The tiles would quickly detach from the floor or wall, they add, noting that polymer-modified tile adhesives are the only way to permanently bond these kinds of tiles.

“Thanks to the new technology and the new products used for the Olympic venues, my name quickly gained currency in technical circles after the games,” says Kranz. That was the beginning of an exceptionally successful career: trade organizations from all over Germany invited him to speak, Ardex promoted him to the position of technical manager for the tiles and screeds business, and he earned a degree in civil engineering while continuing to work. And he has served as an expert witness ever since retiring from Ardex – a role he continues to fill to this day.

Adhesion that lasts for decades

The 72,800-square-meter canopy consists of steel cables suspended on 80-meter high pylons and a covering made of acrylic glass panels.

Many of the tiles laid in the early 1970s in the kitchens and bathrooms of the Olympic Village are still there – bonded in place as firmly as ever. What’s more, the pillars in the Olympic Stadium have coped with the large crowds attending events such as the 1974 World Cup, Bayern Munich soccer matches (who played there for many decades), and Rolling Stones concerts (which have been held there seven times to date).